An interdisciplinary team of academics explored whether co-inventing novel technologies with local users could help tackle digital inequity. It did.

Now they want to take their ideas further.

As new digital technologies continue their rapid, relentless transformation of the way we live and work, more and more people are being left behind; the elderly, the econimically disadvantaged, the disconnected, or people living on a wide spectrum of health issues and disabilities.

Digital exclusion occurs at the intersection of a variety of factors, not least when times are economically tough. Often, it occurs – and continues – simply because of the conditions where someone lives.

In the UK, nearly 17 million people do not possess the digital skills needed for everyday life. Around 6% of the population remains unconnected from the internet entirely, and one-in-four people classify themselves as digitally excluded in some form, affecting everything from accessing healthcare or even their own money.

The cost of the quickening pace of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is the digital ostracisation of a large proportion of the population and the personal, societal, and economic consequences that represents.

No-one knows that better than Professor Ray Jones.

While tackling digital inequality has become a hot topic for policy makers more recently – especially with the advent of generative AI – Prof. Jones has been researching the topic for the last 40 years.

He pioneered the first touch-screen health information kiosks in the 1980s – siting them in supermarkets, libraries, and even pubs – and has published more than 300 research papers on the intersection of technology and public health. He was recognised for his efforts with an MBA in 2021.

Now Professor of Health Informatics and Co-Director of the Centre for Health Technology (CHT) at the University of Plymouth on the southwest coast of England, Prof. Jones has been leading an innovative project that has aimed to find new ways to proactively get ahead of the problem.

The idea: radically localise technology development in partnership with end users themselves.

The ICONIC project – which stands for ‘Intergenerational Codesign of Novel Technologies in Coastal Communities’ – has sought to rethink technology innovation by building it from the ground up in a collaborative design process that puts local communities and their specific needs in the driving seat.

The results have been enlightening: Four working technology prototypes that connect users to their environment, each other, and their regional heritage. Now the team is looking to take the next step.

Teaming up to fight digital exclusion

The far southwest of England presents a set of socio-economic conditions that make it an ideal test bed for novel ideas like ICONIC.

Informally comprising the counties of Cornwall and Devon, Plymouth itself sits on the border between the two counties and is the region’s only major urban conurbation. While being home to western Europe’s largest naval base, the city of Plymouth is both relatively small – more than 30 British cities are larger – and relatively disadvantaged, ranking in the top fifth of the country’s most deprived districts.

Beyond the city is a wider region whose population is both older and more sparsely concentrated than the rest of the UK, and one that wrestles with historically poor transport interconnectivity with the rest of the country. Digital exclusion, therefore, is already a pressing concern.

“With Plymouth and the southwest being rural and coastal, there’s economic disadvantage, the disadvantage of being peripheral, but also the disadvantages for older people who don’t have the skills and the access to technologies,” says Prof. Jones.

“We have been looking at ways to address that.”

Beginning in 2022 and now concluding, the ICONIC project has been a continuation of a years-long academic effort led by Prof. Jones and the CHT that began with other initiatives proving the value of a codesign methodology to foster localised technology innovation.

The ‘eHealth Productivity and Innovation in Cornwall’ (EPIC) project worked to foster and grow the region’s enterprise R&D ecosystem in the area of digital health, while the ‘Generating Older Active Lives Digitally’ (or GOALD) project focused on using digital tools to support the wellbeing of older people.

Dr Rory Baxter, working alongside Prof. Jones on all three initiatives as part of a diverse and multidisciplinary team, says the process of extending academic pursuits directly into the community – and involving end-users directly in the development of new ideas – has been revelatory.

“I was lucky enough to join Ray and the CHT team on the GOALD and EPIC projects, and they were hugely beneficial – they gave me a real insight into the importance of codesigning digital health tools. The work has widened my horizon in terms of rampant digital exclusion, and ICONIC has shown how we can work in a more applied way to address the issue successfully.”

We’re in this because we want to make a difference

The CHT’s ability to marshal a widely interdisciplinary academic team has been key to its success, says Prof. Jones, as was the initial groundwork to enrol a multigenerational and representative cohort of volunteers from the region to participate in the codesign process.

“The team includes people from the arts, from health, from engineering, robotics, AI – really across the whole university – and that’s quite typical of what we do at CHT,” he says.

“The argument goes that the southwest isn’t great in tech. You know, we haven’t got Silicon Bay just yet. But what we have got is a lot of great resources in terms of heritage and the environment. So, let’s use what we’ve got to address the digital inequalities issue.”

Funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the ICONIC project involved forging links with a wide range of regional community organisations, charities, businesses, and education providers to both build its cohort of participants and provide focused opportunities for the technologies it would look to develop.

Those technologies would ultimately aim to connect people to the region’s unique heritage, the environment, and to community resources.

The technologies

After a period of consultation with its many partners and navigating the difficult task of constituting a stable group of intergenerational volunteers, the ICONIC team focused on four technologies for development: A virtual reality (VR) application in the context of heritage locations; underwater telepresence in connection with the region’s rich coastal environment; a social videogame focused on locally relevant conservation; and AI voice assistance to connect users to local services.

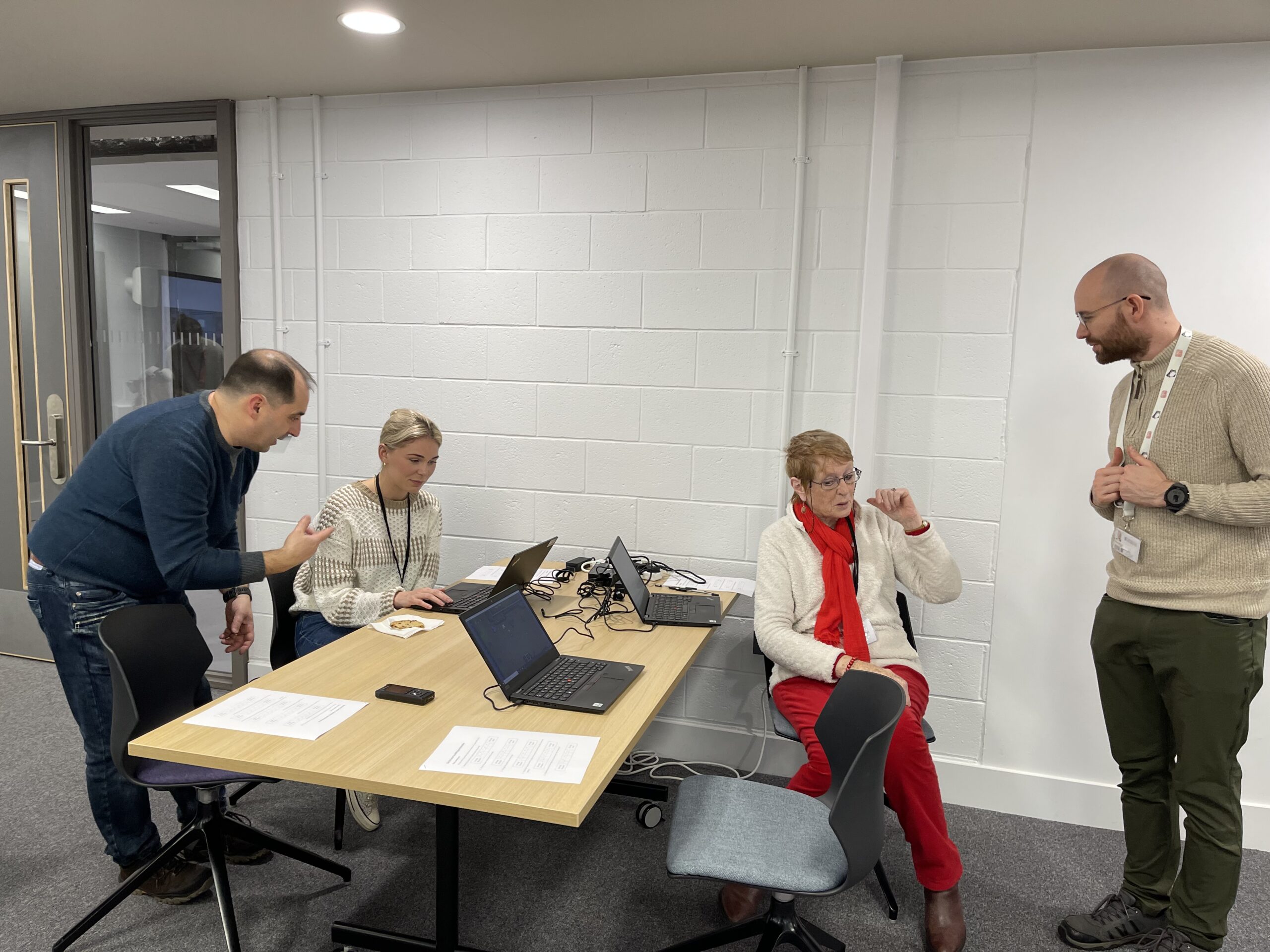

Programmes of workshops, each including a different set of volunteers and led by CHT researchers Oksana Hagen and Dr Marius Varga, began in August 2023 and continued until the end of 2024.

The workshops began by introducing participants to the core concepts and opportunities of the respective technologies, before gradually homing in on specific applications, guided by the users. Between workshops, the CHT team would work on the technologies, solicit further feedback, and iterate them in concert with the groups.

As users’ understanding of the technologies grew, says Dr Baxter, they were able to focus on application ideas that would have the most impact for them in their specific contexts. But the process was, in of itself, a valuable means of tackling a key aspect of digital exclusion – self-imposed digital isolation driven by a resistance to the unfamiliar.

“One of the things that worked really well in the codesign process was breaking down the very essence of what these technologies are,” he says.

“The best example is with the social game. In the first workshop, Marius devised an activity where the participants basically did nothing with technology at all. They just designed their own board game with a pen and paper to get them think about game mechanics: cooperative or competitive, thinking about win-lose states, all the basic properties of any kind of game. And then we were able to get them to think about how that gets integrated into a digital format.”

Dr Baxter explains the team has been able to show how the codesign process not only led to fully realised prototype applications, but also provided an effective, systematic way of introducing technologies to participants in a way that lowered their barriers and reduced their exclusion from them.

As the team now looks to expand its activities further, they can point to a cascading set of benefits in terms of both technology and the people they involve in developing it.

“The process itself gives us a model for broadening people’s usage of technology,“ adds Dr Baxter. “There has been lots of positivity from our participants around how it’s widened their horizons.”

Cascading benefits

Prof. Jones and the CHT team are now actively seeking avenues to continue and broaden the impact of their work, as they analyse the evaluation data and write up their papers.

Each of the four codesigned prototype technologies are working and demonstrable, and themselves ripe for further development. But the process itself is also readily exportable, with each instance of locally codesigned technologies offering the potential to deliver both viable products and compounding community benefits in the area of digital exclusion.

As well as a working multiplayer social game that unites players around seagrass conservation, the CHT team and their codesigners successfully delivered an accessible VR experience that offers an intimate experience of local heritage location Cotehele Hall to those who would otherwise struggle to visit. The team has also taken visitors to Plymouth’s renowned National Marine Museum underwater via educational, interactive video streams into VR headsets, and unveiled an AI voice assistant that conversationally connects local people to help and services in their area via a simple phone call.

“We’re in this because we want to make a difference,” says Prof. Jones. “We want these technologies and prototypes to be used by people more broadly, so now we’re looking to not just maintain and really nurture the fantastic partnerships we already have, but bring in new partners as well.”

Prof. Jones explains the goal now is to attract interest from social-impact investors, sponsors, or funding bodies to help the CHT expand on its success.

“We want people to come with us on this journey, and to invest in it. Not just because it could make a good return, but to develop our ideas and contribute us new ideas now we have proven the academic case for the sorts of results we can deliver.”

Products of codesign: ICONIC prototypes

Gaming Seagrass

The city of Plymouth is a centre of ocean-based science and conservation and his home to the Ocean Conservation Trust. One of the Trust’s key initiatives is Blue Meadows, a project that aims to both conserve and grow vitally important coastal seagrass meadows.

Seagrass is often overlooked both literally and figuratively. It is around 35 times more efficient a carbon store than tropical rainforests, is a habitat for a vast array of fish and invertebrates, and helps prevent coastal erosion. And yet up to 90% of it has been lost in the last 100 years, primarily due to physical disturbance and pollution caused by humans.

The ICONC team and its panel of participants codeveloped the idea of a social game to educate users about this vital local resource and the key principles in its conservation. As well as using the codesign process to upskill participants in their awareness of digital technologies and game mechanics, and thus directly tackle digital exclusion, the eventual prototype would be one that could go on to be a useful tool for broadening awareness of – and even fundraising for – the conservation efforts themselves.

Through the codesign process, the ICONIC team was able to iterate on participant feedback to create a multiplayer game that focused on the growth mechanics of seagrass and reaping the benefits of success. The participants led the game to use non-verbal communication as a game feedback device and boon to its accessibility.

“Seagrass is not just important generally, but in particular to this group of people. We were able to build something together that really resonated with them, but also in a way that introduced them to this technology in a way they had never experienced. It widened quite a few horizons. Now we hope to find new partnerships to help us continue to develop it and widen its impact further."

– Marius Varga

Underwater telepresence

Also in conjunction with Ocean Conservation Trust and its National Marine Aquarium, the ICONIC team launched a workstream that aimed to connect local people with an underwater environment that, despite being next door, they may have never experienced firsthand.

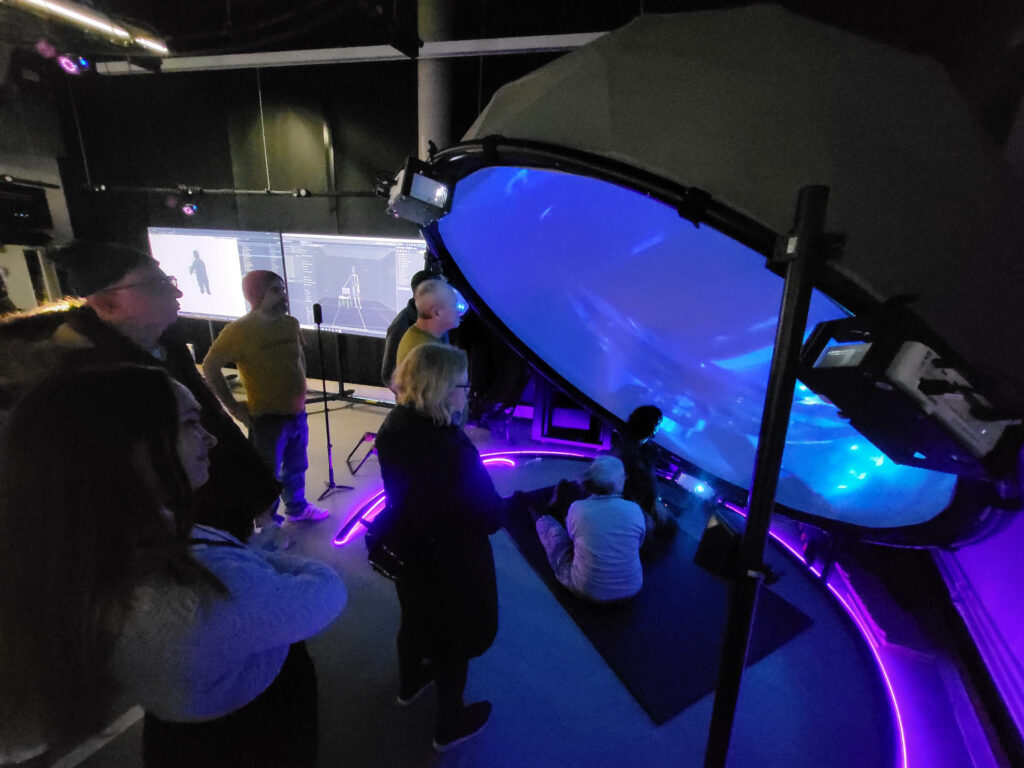

The initiative focused on accessibility, ensuring that users – whether in care homes, schools, or other settings – could engage with underwater spaces through immersive technology. The primary concept involved a VR headset streaming video from a 360-degree camera submerged in an aquarium tank, allowing participants to observe marine life in a controlled environment while interacting with the experience through AI-powered species identification.

A key finding from the codesign process was the strong preference for live streaming over pre-recorded footage, particularly if the technology were deployed in open water rather than an aquarium. Insights came from testing an underwater robot, which participants operated remotely in Plymouth Sound. While logistical challenges such as weather conditions and infrastructure requirements ultimately made real-time streaming difficult, the project demonstrated the potential for future development, which the ICONIC team is now keen to explore with new partnerships.

Despite initial concerns about complexity, the experience proved highly engaging, suggesting that interactive telepresence could be a valuable tool for education and tourism, as well as digital engagement in the local community. Future development could involve refining AI capabilities, improving live-streaming infrastructure, and exploring commercial applications, such as tourism experiences or conservation awareness programs.

“Participants recognised the therapeutic benefits of viewing underwater spaces, so requested both a relaxing, passive version of the experience as well as an interactive learning experience.”

– Oksana Hagen

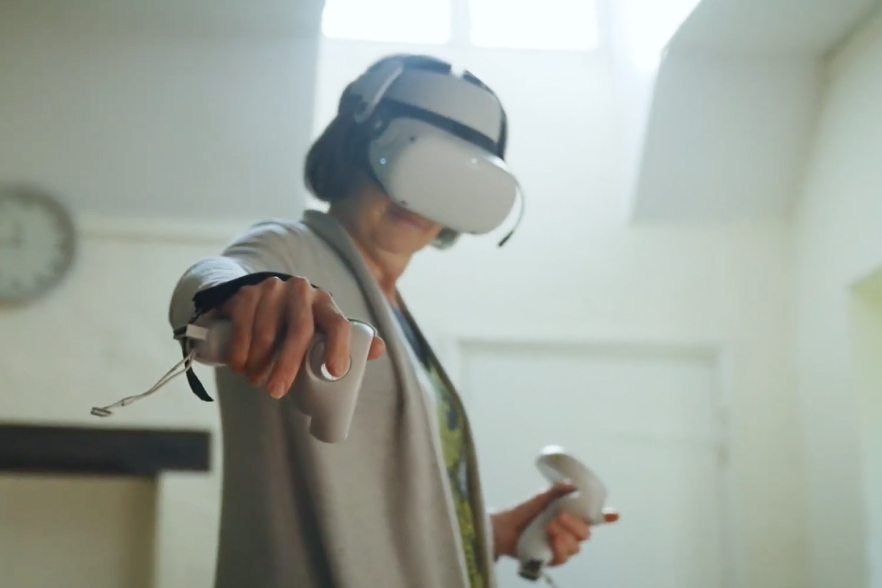

Extending reality into the past

The ICONIC team had a powerful asset at its disposal when conceiving technology applications that would resonate with project participants: The region’s unique cultural heritage.

A partnership with the National Trust and its late-medieval-era Cotehele estate became the focus for a technology application could create an immersive experience of the estate’s magnificent Tudor house, complete with tapestries, armour, and historic objects.

The project used 360-degree video and interactive VR elements to allow users to explore historically significant areas of the manor, including spaces normally inaccessible to visitors.

A key challenge was balancing historical authenticity with user interaction. The team captured six unique locations within Cotehele, including a restricted area with a centuries-old floor, using 360-degree imaging. Participants tested these immersive environments and provided feedback on usability and engagement. One major insight was the desire for interaction – users wanted to touch walls, examine artefacts, and move freely within the space.

To improve accessibility, the project refined VR hardware, replacing standard headset straps with custom designs that distributed weight more evenly, reducing discomfort. Controllers were also adapted for users with limited dexterity, allowing simplified interactions with objects in the virtual environment.

The final prototype featured a multi-sensory experience, incorporating visual, audio, and haptic feedback. Users could pick up historical artefacts, including swords and mugs, and even engage in playful interactions, such as pretending to eat virtual cheese. The project also explored gamification, with participants suggesting escape-room-style puzzles based on historical clues.

Now visitors unable to fully explore this treasure of their historic neighbourhood could gain an informative, entertaining experience like no other.

“We wanted to give users an experience of being in the space, rather than just recreating it. We made absolutely everything interactable. The ability to interact with objects and navigate freely in a space you can’t normally access made the experience more meaningful, especially having improved the accessibility of the devices. There is so much more we could do, and we are looking forward to expanding the amount of content we can include, as well as potentially using it in other historical contexts.”

– Marius Varga

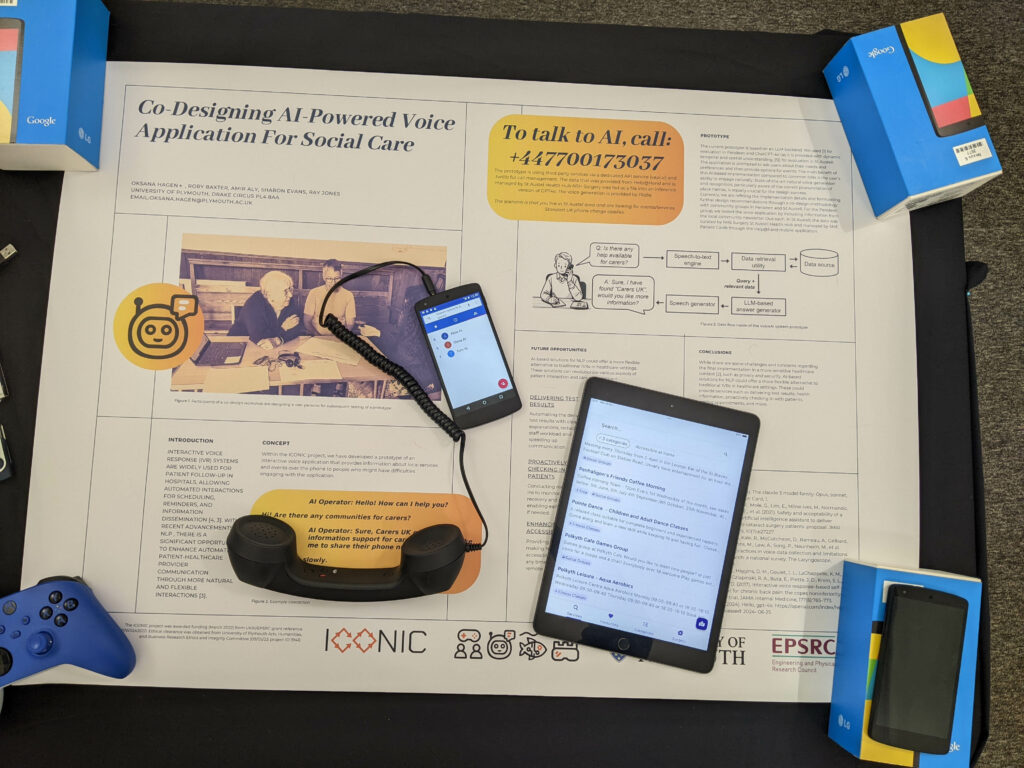

A local AI voice assistant

Perhaps the ICONIC team’s most direct application tackling the digital exclusion problem, its AI voice assistance workstream led to the creation of an AI-driven voice-based system for social prescribing.

Designed for individuals who prefer traditional phone communication over digital interfaces such as chat, the concept is to connect users to local services and activities through a natural-sounding AI assistant. The project leveraged cutting-edge AI technologies, including GPT-4, to ensure intuitive and accurate interactions.

Participants tested prototypes and provided feedback on usability, voice characteristics, and conversational style. While the assistant was designed to prioritise functionality, offering clear and reliable information, participants also expressed interest in a more engaging assistant capable of light banter, hinting at a deeper social purpose.

The system operates via a simple phone number, making it accessible to users without internet access or smartphones. It uses advanced semantic processing to match user queries with relevant database entries, ensuring accurate recommendations even when phrasing differs. For example, it can link “activities for kids” with “youth clubs” based on conceptual understanding.

While the prototype clearly demonstrated significant promise, it is ripe for much expanded functionality including secure integration with public services, community organisations and other service providers.

"Participants were amazed by how natural the assistant sounded, often mistaking it for a real person. This shows the potential for AI to bridge the gap for digitally excluded individuals. It’s a technology that could have so many further applications and be able to reach a very large number of digitally excluded people.”

– Oksana Hagen